Continuing our series on the icons of the Great Feasts of the Eastern Rite Catholic, and Orthodox Churches.

(click on the picture for a larger image)

This Sunday, June 19 is Trinity Sunday in the Western Church. In the Eastern or Orthodox Church there is technically no separate feast of the Trinity; what we call the day of Pentecost is called Trinity Sunday in the Eastern Church. The Holy Trinity is central to “Pentecost” which celebrates the substantial presence of the Holy Spirit in the Church. The icon of the Holy Trinity is brought out for veneration on Sunday and the icon of the Descent of the Holy Spirit is brought out on the next day, Monday (Monday of the Holy Spirit).

The descent of the Holy Spirit is considered the culminating action of the Holy Trinity -Father, Son, and Spirit- in the redemption of the world. The descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost is the final fulfillment of the promise made to Abraham. All three Persons of the Trinity take part in every providential action relative to the world. The Father is Creator of the world and does all things through the Son –the Redeemer- with the participation of the Holy Spirit –the Sanctifier. It is through the Son that we know the Father and through Him that the Spirit was sent to us. The descent of the Spirit at Pentecost is the revelation to the world of the mystery of the Trinity, consubstantial, undivided and yet distinct. (In Eastern Orthodox theology the Father sends forth the Son and the Holy Spirit. The Spirit is sent into the world through the Son, not by the Son.)

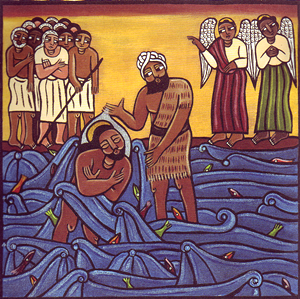

The icon of the Holy Trinity, therefore, is closely associated with Pentecost in the Eastern Church. The oldest visual expression of the Trinity is seen in the Old Testament story of the Hospitality of Abraham in which three men appear as angels to Abraham near the oak of Mambre (Genesis 18). This is the first appearance of God to man and begins the promise of redemption which will be finally fulfilled with the descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. The Holy Trinity icon binds together the beginning of the Old Testament Church and the establishment of the New Testament Church.

From ancient times an image associated with the actual location where three men appeared to Abraham depicts the three as angels seated at a table under the oak tree. Abraham and Sarah serve them; their house is in the background. A servant killing a calf was often included in the scene. The scene varies from icon to icon depending on the interpretation stressed. Some theologians see the story as the appearance of the Godhead, all three Persons of the Trinity. Others saw it as an appearance of the Second Person accompanied by two angels. Since each Person of the Trinity possesses the fullness of the Godhead, the image of the Son with two angels could be interpreted as the Trinity. The point is that Abraham sees God, as much as anyone could possibly see God. The three men are often seated at table next to each other as equals; unified and yet distinct. They often are rendered in the same colors to emphasize their shared nature. In other compositions the figures are arranged in a triangular composition with the central angel placed higher in the design.

The most revered icon in the Orthodox Church of the Holy Trinity is something like the second type and was painted by (written by) St. Andrew Rublev most likely between 1408 and 1425. Abraham and Sarah are not shown in this icon and a mountain joins the house and oak in the background. The historical details have been pared down to a minimum to stress the dogmatic meaning.

The composition of Reblev’s icon is organized according to a circle (see diagram). The angels appear in a circle which unites them into one flowing movement. As a result the central angel ends up higher than the other two but does not dominant over them.

… Circular movement signifies that God remains identical with Himself, that He envelops in synthesis the intermediate parts and the extremities, which are at the same time containers and contained, and that He recalls to Himself all that has gone forth from Him. The two flanking angels incline their heads toward the central figure but all three indicate with their hands the chalice on the table (an altar) holding the head of a sacrificial animal symbolizing the voluntary sacrifice of the Son. In this way the covenant with Abraham is bound, in this icon, to the covenant in Christ’s blood (1)

The angels are very similar and yet differences are easily noticed. The Father (on the left) is more reserved and reticent and rendered in sober and difficult to identify colors. The historical detail of the central angel with the traditional purple color of the chiton and blue cloak identify this figure as the Son while the green color of new growth and renewal of the angel on the right indicate the Holy Spirit. For Pentecost, churches and houses in the East are traditionally decorated with green branches, plants and flowers expressing symbolically the power of the Holy Spirit to renew the face of the earth. Notice that the blue color of the Son’s cloak is echoed in the flanking figures indicating a shared nature.

This is the classic iconic image of the Holy Trinity.

…………………………………………………………………………………

Reference

Leonid Ouspensky & Vladimir Lossky, The Meaning of Icons, (Crestwood, Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1994) pp 200-205

Notes

1 On Divine Names, St. Dionysius the Areopagite, P.G. 3, col. 916 D as cited in The Meaning of Icons, Leonid Ouspensky & Vladimir Lossky, (Crestwood, Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1994) p202