(Click on picture to see a larger image)

In the Western and Eastern Churches, the feast of the Assumption of the Mother of God is August 15. In the Eastern Church the solemnity is known as the Dormition (the falling asleep) of the All Holy Mother of God. The Assumption of Mary into heaven is a matter of proclaimed dogma in the Catholic Church. It is not a dogma in the Eastern Church and yet it is solidly part of the traditional faith of the Orthodox that the grave and death could not possibly hold the “Mother of Life.” To the Orthodox, the Dormition is a mystery that is held in the “inner consciousness” of the Church and is not “for the ears of those without” for fear that exposure might result in profanation. It can be contemplated only by the “inner light of Tradition.” Unlike the Resurrection and Ascension of the Lord, the Dormition and Assumption of Mary was not part of the apostolic preaching.

The feast of the Dormition actually commemorates two distinct and yet inseparable moments in the faith of the Eastern Church: the death [1] and burial of the Holy Virgin, and her resurrection and assumption. Some refer to this as a second Easter, “the secret first fruit of eschatological consummation” as the Church celebrates –before the end of time– the glory of the age to come; the end of man is realized in the present in the assumption and deification of the All Holy Mother of God.

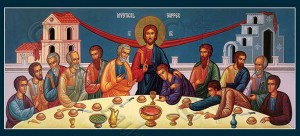

The classical image of the Dormition has the Holy Mother lying on her deathbed surrounded by the apostles who have come, miraculously from all the ends of the earth. Peter and Paul stand at the ends of the bed with Peter swinging incense on the left. Bishops stand behind the apostles, among them St. James (“the brother of the Lord”) and the first bishop of Jerusalem. They stand out with their flatten bodies sporting patterns of black crosses on white robes. Sometimes groups of women, representing the faithful of Jerusalem, join the apostles forming a kind of select group gathered to witness the sacred mystery of the Dormition.

Christ, in a mandorla, looks upon his mother and has gathered up her glorious soul in his arms. In this icon we can also see the moment of her bodily assumption: she appears above the mandorla of Christ in her own mandorla. Angels lift her up to heaven. The mandorla, a symbol of divinity, is used here to indicate the deification of the Most Holy Mother of God and calls to mind our hope for our own deification at the end of time. In Christ’s mandorla we see heavenly seraphim, cherubim and angels.

In some icons (as we see in this one) a fanatical Jew has dared to profane the holy bed and has his hands sliced off by a sword wielding angel. The inclusion of the story in the foreground indicates the Church’s view that the Dormition can only be contemplated in light of sacred Tradition.

The feast of the Dormition is thought to have originated in Jerusalem. The Assumption of the Virgin was depicted on a sarcophagus in Saragossa at the beginning of the 4th century. But, as a feast, it was already widely celebrated beginning in the 6th century and so no doubt had its beginning well before that. St. Gregory of Tours is the first witness in the West to a formal celebration, then commemorated in January. Under the Emperor Maurice (582 – 602) the date of the feast was fixed as August 15.

………………………………………………………….

Notes

[1] “The Orthodox Church teaches that Mary died a natural death, like any human being; that her soul was received by Christ upon death; and that her body was resurrected on the third day after her repose, at which time she was taken up, bodily only, into heaven. Her tomb was found empty on the third day. Roman Catholic teaching holds that Mary was “assumed” into heaven in bodily form. Some Catholics agree with the Orthodox that this happened after Mary’s death, while some hold that she did not experience death. Pope Pius XII, in his Apostolic constitution, Munificentissimus Deus (1950), which dogmatically defined the Assumption, left open the question of whether or not Mary actually underwent death in connection with her departure, but alludes to the fact of her death at least five times. Both churches agree that she was taken up into heaven bodily.” Source

Reference

The Meaning of Icons (revised edition), Leonid Ouspensky and Vladimir Lossky, (Crestwood, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1989)

The beheading of St. John the Baptist, whom Herod ordered beheaded about the time of the Feast of the Pasch; but his memory is solemnly kept on this day, August 29, on which his venerated head was found for a second time. It was afterwards translated to Rome and is preserved in the church of St. Silvester in Capite and honoured by the people with great devotion. (from The Roman Martyrology)

The beheading of St. John the Baptist, whom Herod ordered beheaded about the time of the Feast of the Pasch; but his memory is solemnly kept on this day, August 29, on which his venerated head was found for a second time. It was afterwards translated to Rome and is preserved in the church of St. Silvester in Capite and honoured by the people with great devotion. (from The Roman Martyrology)